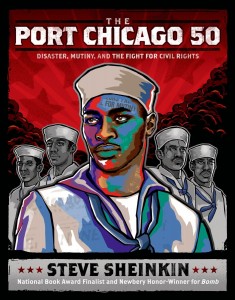

Why I Picked It Up: There were several things that came together to confirm that I’d made a good choice when I picked up this book. I found out about it during a session at the recent Texas Council for Teachers of English Language Arts and Reading (TCTELA) conference about non-fiction. The cover flashed up on the presentation screen as one of the suggestions for non-fiction read-alouds, along with Bomb, Sheinkin’s award-winning novel about the atomic bomb (which is definitely on my to-read list!). I recognized Sheinkin’s name from when I read Lincoln’s Grave Robbers, and I remembered how much I enjoyed reading that one, so I diligently wrote down the title. A few days later, I was looking through the Lone Star Reading List for 2015 to try and get a jump on the reading for next year’s Battle of the Books, and there it was again – Port Chicago 50 was on the list! One quick trip to the library later, I started reading.

Why I Picked It Up: There were several things that came together to confirm that I’d made a good choice when I picked up this book. I found out about it during a session at the recent Texas Council for Teachers of English Language Arts and Reading (TCTELA) conference about non-fiction. The cover flashed up on the presentation screen as one of the suggestions for non-fiction read-alouds, along with Bomb, Sheinkin’s award-winning novel about the atomic bomb (which is definitely on my to-read list!). I recognized Sheinkin’s name from when I read Lincoln’s Grave Robbers, and I remembered how much I enjoyed reading that one, so I diligently wrote down the title. A few days later, I was looking through the Lone Star Reading List for 2015 to try and get a jump on the reading for next year’s Battle of the Books, and there it was again – Port Chicago 50 was on the list! One quick trip to the library later, I started reading.

Why I Finished It: Why not??? As he did with Lincoln’s Grave Robbers, Sheinkin truly made history into a story with this book. He seems to have a knack for finding the lesser known, but certainly not less interesting stories that I don’t remember learning about during my school days, even as a history minor in college. After browsing his website, I learned why. Sheinkin used to write history textbooks, and during his research he would come across all kinds of really interesting stories. Of course, these were not allowed into the textbooks, and so he vowed to use them to write a book one day. I’m so glad he did! He has several other books, which I’m already looking up in my library’s catalog and I’m really anxious to read!

I knew nothing about the Port Chicago 50 – the 244 black men who refused to load ammunition onto boats at a Navy shipyard after a massive explosion caused by unsafe and unfair working conditions. I had no idea how instrumental the following court case and events were in leading up to what we know as the civil rights movement and ending segregation in the United States armed forces. As I was reading, I kept having to remind myself that I was reading about World War 2, especially as characters that I am used to reading about in connection with civil rights in the 1960s, such as Thurgood Marshall, made an appearance. We tend to think of history as chunks of time, or chapters in a textbook, consecutive, but separate. This book really reminded me of the continuity of history, that themes like prejudice and equality transcend time and even sometimes serve as a connection or transition into the next era.

Oh, and of course, Sheinkin’s signature approach to blending primary sources with the text is amazing! Read more about primary sources below.

Who I Would Give It To: History buffs of all ages. This is definitely a book that teachers could use to lead into learning about the civil rights movement since it is so interesting and makes you want to know more! It could also be a springboard into getting students to read more non-fiction, since it proves that non-fiction doesn’t have to be boring!

Integration Ideas

Primary Sources

The Library of Congress defines primary resources as “the raw materials of history – original documents and objects which were created at the time under study.” Primary sources can include personal letters, journals, newspapers, books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, drawings, paintings, songs, and cartoons, and can be powerful tools to enhance your study of history by engaging your students, promoting critical thinking, and helping them construct meaningful background knowledge.

Lucky for us, Sheinkin has already done the hard work of compiling those raw materials that connect to this particular story. Help students realize how much life primary sources bring to a story by pairing Port Chicago 50 with another traditional historical account, maybe from a textbook. Which story are you more interested in? Which story makes you want to ask more questions? Which story is more memorable?

Challenge students to “beef up” a traditional story from their textbook with primary sources and share it with the class!

In a recent post, I shared some places for finding historical images, but here are two other sources for finding even more primary resources:

American Memory Project – from the Library of Congress, this collection provides access to all types of primary sources that document the American experience. Through this project, they hope to “chronicle historical events, people, places, and ideas that continue to shape America.” You can browse by topic or collection and they have really great resources to help teachers.

DocsTeach – from the National Archives, this tool allows the teacher easy access to thousands of primary source documents selected from the National Archives. You can choose to build your own collection to use with students, or choose from the collections and activities already created. iPad app also available.

Theme

Prejudice and equality are common themes throughout history, defining many conflicts and events. Select several time periods and have students determine what prejudices were present and the impact it had on history. Talk about the differences and similarities between, for example, the Civil War and World War II, or the civil rights movement and women’s suffrage. Use the commonalities to help students make connections and experience the continuity of history for themselves.

Technology

The official Port Chicago 50 teacher’s guide suggests that students hold a Civil Rights forum in the classroom, with each student being assigned the role of one of the characters in the story. The students, through group and independent research, should be prepared to answer questions about their role in the events of the Port Chicago explosion and trial, as well as their views. You can get more specifics, including a “cast list,” from the guide.

This is a fabulous activity that encourages students to think creatively and really develop a deeper understanding of the issues facing their character. I would take it a few steps further, in conjunction with the theme activity from above. Instead of limiting the students to characters from this one event discussed in the book, have them choose (or assign) people from a wider selection of history or even include fictional characters.

Using a learning management system (we like Edmodo!), have students begin to interact with each other as those characters from different parts of history. Pose open-ended questions to prompt discussion and provide guidance for student research (if they don’t know how their person would answer that question, they’ll have to go find out!).

Super post! “American Memory” is slowly being phased out as a project, but all the content remains on the Library of Congress website. I have begun to explore the old American Memory materials through the much improved search options from the loc.gov homepage, where you not only see helpful dropdown keyword suggestions, but you can also use the “facets” on the lefthand side of results screens to narrow by date, format, and more. That approach also helps me locate the thousands of additional online primary sources that were never part of American Memory.

My other favorite approach is to go straight to loc.gov/teachers to find the wealth of materials assembled with classroom uses in mind. For high quality, spoonful-sized doses of the best in teaching ideas using primary sources, I absolutely love the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog: http://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/

Thanks Mary! I’m sad that the American Memory Project is going away, but so glad they seem to be making it MORE user-friendly to find quality resources. Thanks for sharing your additional information as well!